No resilience without solidarity

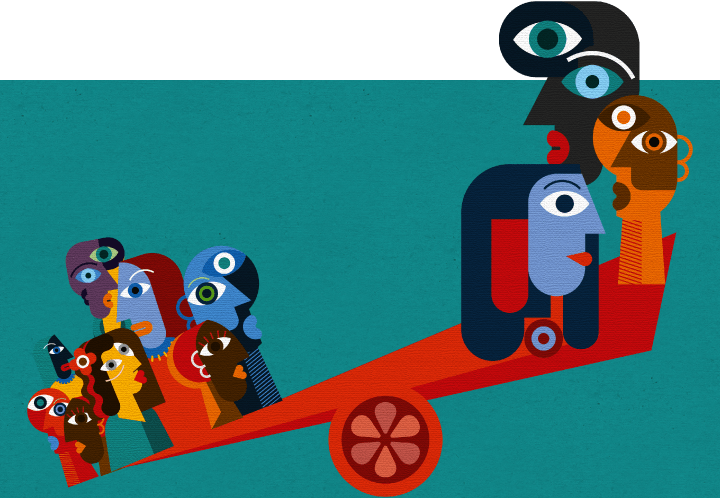

In a newly published paper, a team of researchers from Liverpool and Lancaster universities argue that there is a need to rethink place-based resilience as the capacity of all individuals and agencies living, working, and operating within a neighbourhood to take collective action to address local, upstream determinants of health inequalities. The authors argue that the currently predominant concept of ‘community resilience’ is at best deficient as a basis for designing and undertaking public health interventions, and at worse it contributes to the reproduction and exacerbation of the health inequalities it purports to address. Its central weakness is that it promotes a narrow focus on the resilience of people living in relatively disadvantaged places and obscures the crucial relational components between residents and the diversity of other social actors also shaping the place.

In their new paper, the authors present an overview and an evaluation of the Neighbourhood Resilience Programme (NRP), an action research programme built on the concept of ‘neighbourhood systems’ resilience and undertaken in partnership with people and organisations in nine relatively disadvantaged areas in the North West of England between 2015 and 2019. The NRP sought to bring neighbourhood system players (residents, public sector professionals, businesses, VCFSE organisations) together, and to challenge and change traditional power dynamics between them so that more equitable and inclusive social connectivities and governance processes could emerge. Resilience in the NRP was seen as a collective capacity emerging primarily from social connections and governance processes that engage everyone with a stake in a neighbourhood.

Most prominently, the NRP operationalised ‘neighbourhood systems’ resilience through:

1) open, shared spaces for collective governance. A particular concern of the NRP was to document and harness all forms of knowledge (e.g. academic, professional) and in particular, the knowledge emerging from lived experience. Resident-led, participative enquiries with local residents working as ‘peer researchers’ captured local knowledge, experience, and wisdom which were then synthesised with other types of knowledge;

2) a dedicated infrastructure for supporting public participation and involvement through the Community Research and Engagement Network (COREN). Local agencies (the COREN organisations) were commissioned to address barriers to participation and to promote enabling conditions for meaningful involvement in the NRP;

3) undertaking collective action for change. Different neighbourhoods identified their own priority topics – e.g. healthy streets and children’s communal play spaces, social isolation, household debt – in which structural adversities needed to be addressed and resilience capacities enhanced. In each neighbourhood, small-scale, local interventions on the topics targeted were participatively designed, undertaken, and evaluated.

A mixed-method evaluation of the NRP (reported in the paper) found beneficial effects in six resilience-related domains: perceived influence on local decision-making, social connectivity in neighbourhoods, cultural coherence, economic activity, and the local environment. These findings support the argument for a shift away from interventions that seek to solely enhance the resilience of communities to interventions that recognise resilience as a whole systems phenomenon. Systemic approaches to resilience can provide the underpinning foundation for effective co-produced local action on social and health inequalities, but they require intensive relational work by all participating.

This post was originally published on the LiLaC website.